It is, after all, not man but the universe that is subtle.

—Barry Lopez

Why do wolves howl?

In Of Wolves and Men, Barry Lopez offers some clues: they howl “to assemble the pack, especially before and after the hunt; to pass on an alarm, especially at the den site; to locate each other in a storm or in unfamiliar territory; and to communicate across great distances.” Howling after a chase might mean a celebration of food, prowess, or camaraderie. Some have chalked it to restlessness, anguish, or loneliness.

In the end, it’s a mystery.

This, of course, strains the Western mind. But perhaps these things are irreducible. If crying is an expression of humanness—a lament, a joyful requital of effort, or both at once—perhaps howling is best thought of as an expression of wolfness.

Or maybe each is its own expression of the beautiful fragility of life; two smoke signals from faraway campfires.

Or perhaps not so faraway. The Nunamiut, a semi-nomadic people who live in the deep Arctic, pay close attention to wolves as signals for where caribou are going. They must; any hint contributes to the hunt. This passage paints a funny contrast with Western obliviousness:

When the Nunamiut hunter goes out, he leaves his personal problems behind, as though they were a coat he had left on a hook. He slips, instead, into a state of concentrated, relentless attention to details: the depth of track, the bend of grass along trails in a certain valley, the movement of ravens in the distance. It is the custom of most biologists, on the other hand, not only to bring their mental preoccupations into the field but to talk about them while they are walking along. Inuit rarely speak when they are on the move and are inattentive to questions, giving only brief answers.

Something like a dad brushing off his clueless kid. Not right now bud.

The wolf, too, lives on the edge of possibility: in the blistering cold, hunting for a living. Its form has been carved by the relentless blizzard of its existence. Its voice sings in harsh, haunting tunes, and its body—black lips against a white muzzle, streaks of mascara around the eyes and ears—scrawls emotions in stunning calligraphic style.

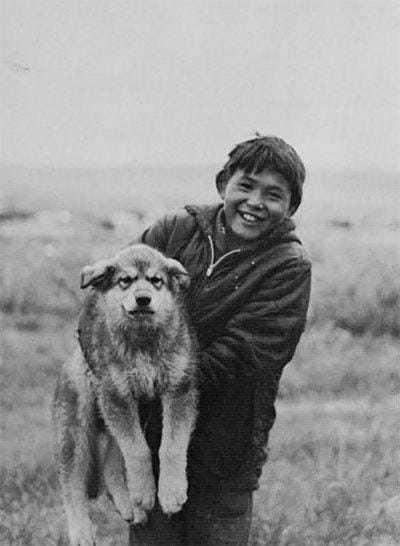

It’s no wonder the Nunamiut look at wolves with such reverence. In the three years Robert Stephenson lived with the Nunamiut, they never said a harsh word about wolves, even as they competed with—and killed—each other.

Their sense of kinship, Lopez points out, is no accident:

They eat almost the same foods—caribou, some sheep and moose, berries, not much vegetable matter. The harsh environment requires of them both the same stamina, alertness, cooperativeness, self-assurance, and, possibly, a sense of humor to survive. They often hunt caribou in the same way, anticipating caribou movement patterns and waiting at likely spots to ambush them.

Or in the words of an old Nunamiut man, Amaguk, the wolf,

is like Nunamiut. He doesn’t hunt when the weather is bad. He likes to play. He works hard to get food for his family. His hair starts to get white when he is old. Young wolves, just like Nunamiut, run around in shallow melt ponds scaring the ducks.

And Amaguk is tough, living at fifty below zero, through blizzards, for months without caribou. Like Nunamiut. Maybe tougher.

This behavior can seem eerily human: playing tag with crows, teaching pups to stay put, getting into fights due to misunderstandings, even staring at water as it flows around their ankles.

Like us, their personalities are distinct. A wolf pack can contain “autocrats, petulant individuals, or even cretins; and the personalities involved may make one pack more Prussian or austere in its organization than another.”

When asked who knows more about the forest at the end of their lives, wolves or men, the old man responds, tersely, “The same.”

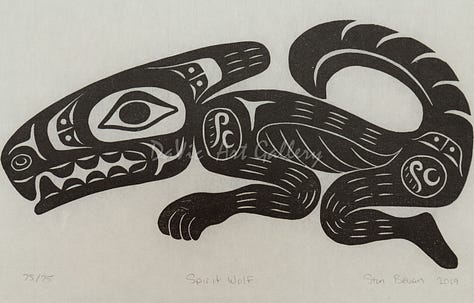

The idea of “spirit worship” might seem strange to us, but to people living among animals, learning to embody their qualities is a practical matter. The wolf is esteemed not as a divine being, but because it lives by the same imperatives as a hunter: he must “be strong as an individual, and submerge his personal feelings for the good of his tribe.”

The Nunamiut are thrust into the same bone-chilling environment of wind and snow. The wolf assembles around the howl, and the Nunamiut, in turn, assemble around the essence, or spirit, of the wolf.

City-dwellers, too, are thrust into our own trials. The Arctic hunter can tell his son what to look for: increasingly, we can’t. We howl—each in our own way—from our lives of quiet desperation, and are often met with silence.

This month has been a desolation of meaning. I’ve argued with loved ones who live in different worlds of information, sometimes to the point of tears. Is there a way we can reach out to each other, in this winter? Can our voices ring in the moonlight, or will they be drowned out by the blizzard?

As divided as we are, can we call out to each other? Can we assemble the pack?

—

While wolves’ scent marks are often thought to just “mark territory” to deter outsiders, Lopez observes that they’re mainly used to coordinate their internal network. They signal junctures, dens, traps, anomalies like beer cans.

In modern life, we walk our own disparate paths; we need to find a way to create signals that are legible to others. The best of us embody archetypes of our culture. They are beacons, lenses into ways of the world.

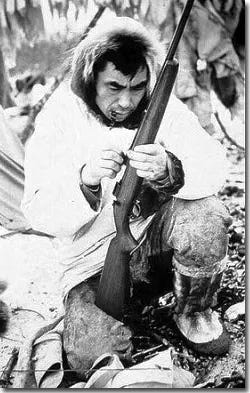

They often lead lives of difficulty, swimming in the fastest and choppiest currents of our society. Like the Nunamiut in the frozen plains, they become equal to their privation. They find their tribe, their rifle, their caribou, in order to face the void; and in moments of anguish and bliss, heartbreak and communion… they HOWL.

These people exist in every walk of life—although palliative care nurses, Marines, and economists have very different “caribou.” In a world that requires the attentiveness of a hunt, you can only become an expert in your own life.

—

Studies show that Inuit people have a greater eye for visual detail than urbanites. Their lives hinge on textures of snow, subtle differences in size and energy of footprints, shifts in the wind near the horizon. We, perhaps, adapt more easily to changes in the tax code, confusing traffic rules.

Can we build an “ecology” of worldviews? What if we started seeing people in other walks of life for the elusive spirits that they are? We could be attentive, respectful, and—in some cases—vigilant. No one holds the answers, because no one lives in the same plane of signals, goals, and stories.

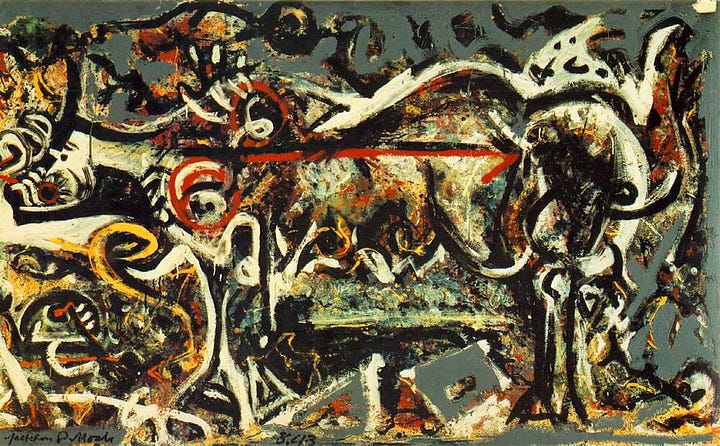

Good art is the howl, the rainbow, the flower of this ecosystem. It’s a signal from one corner of consciousness to the other.

Stories, laws, people: they’re not good because they draw attention or power to themselves; they’re good because of what they facilitate. They’re good because they have an aura of honesty, gratitude, and playfulness, which translates into truth, love, and beauty. They’re good because they gesture at what matters.

—

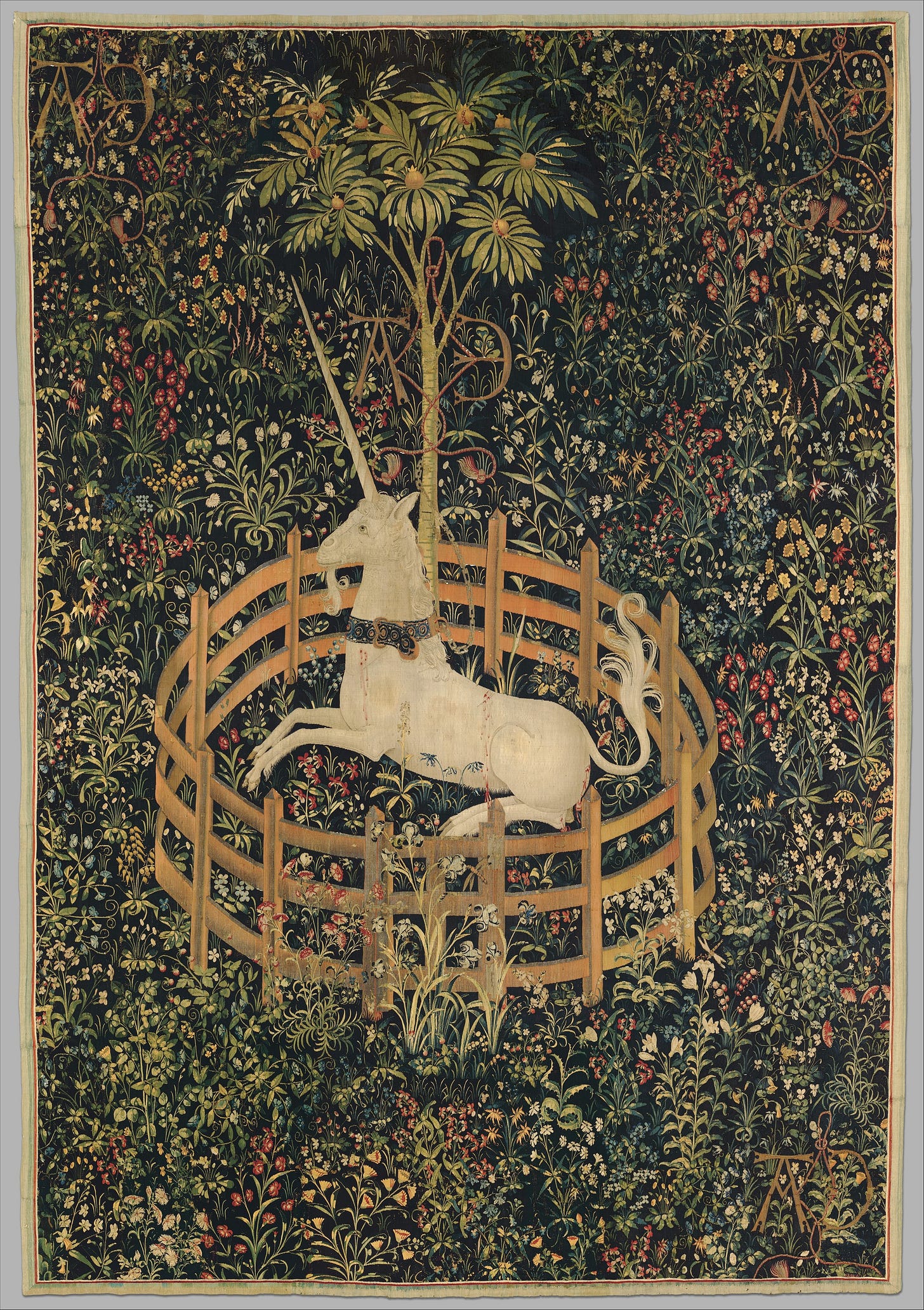

Some people want to capture beauty and put it in a cage. The good artist—like the good naturalist—doesn’t fall prey to this urge. They gesture toward beauty with a sidelong tilt of the head, never pointing or shouting.

They whisper, Look, see that? Let’s keep that alive. ✤

Love this one.

Lovely, Miles.

I have to tell you - one of the silly traffic lights that you posted is from Edmonton, where I live. It is a constant source of annoyance and confusion. And though there are reasons for why it exists as it does, it still makes people bonkers. Its absurdity is one of the few things we can all agree on.