So what’s it like in the real world? Well, the food is better, but beyond that, I don’t recommend it.

…

To invent your own life’s meaning is not easy, but it’s still allowed, and I think you’ll be happier for the trouble.

—Bill Watterson, in his 1990 speech to the graduating class of Kenyon College

A few years ago, I wrote one of my first Substack posts about Calvin and Hobbes. It was a melancholy, probing piece about comic strips as an art form, and how the limiting nature of the medium is a source of its beauty. I want to revisit it now, in a time when I’ve run up against certain limits in my life.

Falling flat on your face gives you a kind of clarity. When your nose is buried in old footsteps, you’re forced to see things from a new point of view. So that’s what I mean to do: “hit the bottom and escape,” as the Radiohead song goes.

This piece is the start of a series of experiments. I’m thinking out loud as I consider branching out into new directions. As always, my hope is that following along is fun and helps you with your own journey.

Here goes nothing!

1 – Eyes of a child

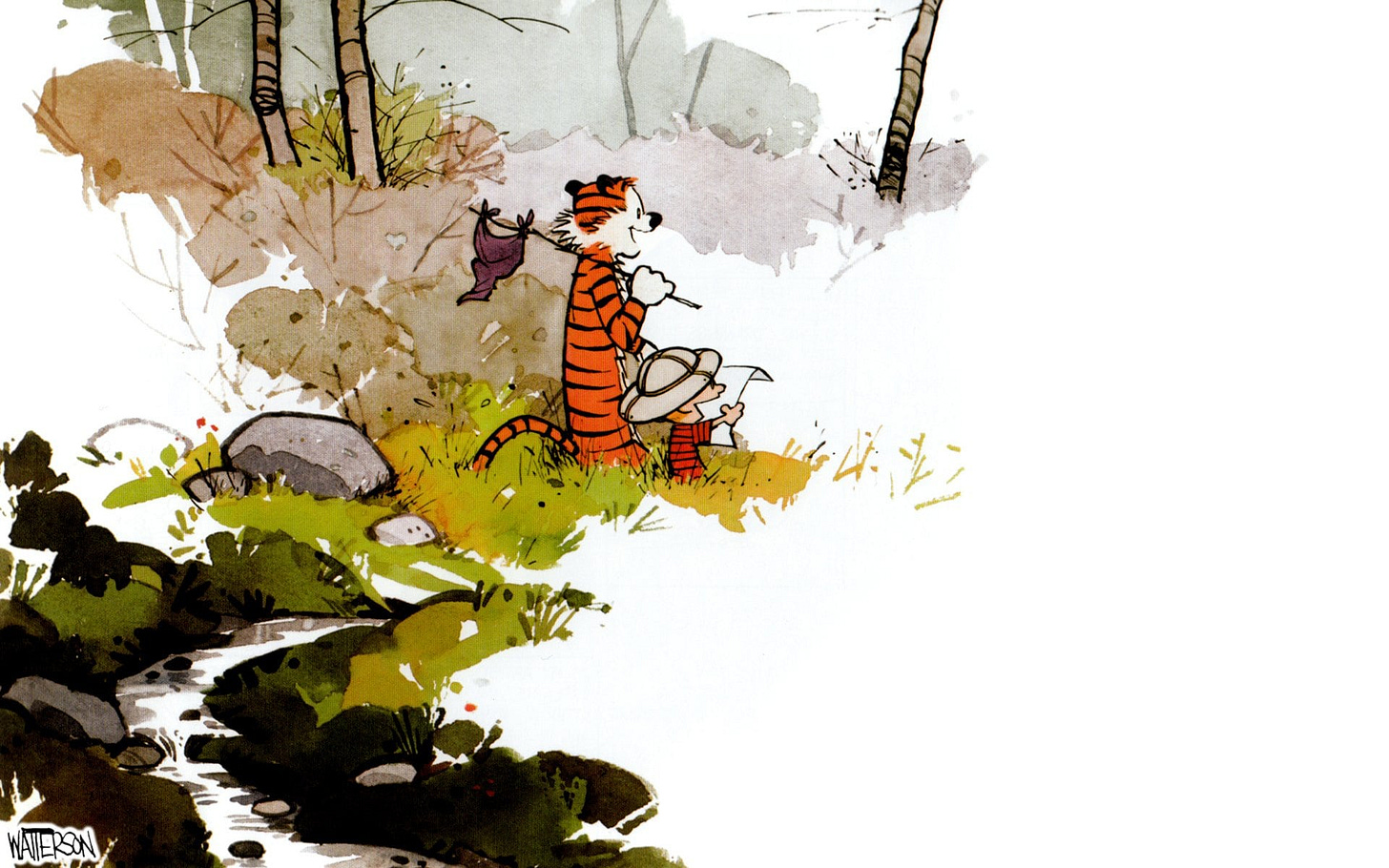

Whenever I feel lost at sea, I open up the Calvin and Hobbes Sunday Pages collection. It overflows with creative wisdom, craft advice, and beautiful artwork—enough to calm the storm.

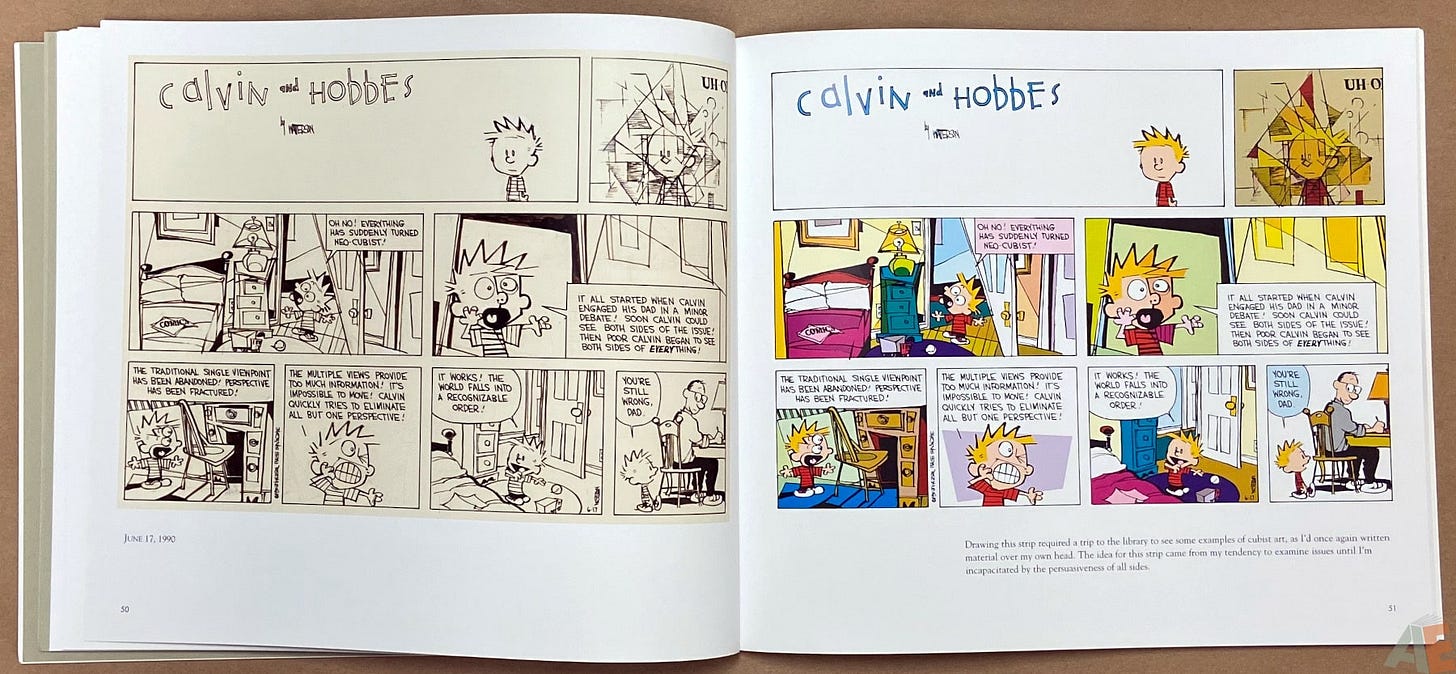

Each spread is a soul-nourishing feast: an original black-and-white strip on the left (complete with masking tape, cutoff markers, and whiteout), and a full-color newspaper rendering on the right. Bill Watterson writes about his creative process with the irreverence and zen-like clarity of a true master.

During the ten years he wrote for Calvin and Hobbes, he produced a comic strip more or less every day. On the weekdays, it was a black-and-white strip with three or four panels—enough for a dose of wit, charm, and honesty; but Sundays were his time to shine. The large, colorful format allowed him to indulge his imagination, to let his characters breathe and express themselves more fully.

The strip’s main characters are Calvin—a naughty adventurous misfit boy—and Hobbes—a haughty exuberant sassy tiger. At times Hobbes appears as a full-fledged tiger, twice as tall as Calvin, conversing and hand-waving and creating mischief, but when others enter the scene, he’s a stuffed animal, carried along like a comfort blanket.

This realm between dreaming and living, childhood and adulthood, companionship and solitude, is familiar. I often find myself torn between the physical world and an imagined one. Fantasies are an inescapable part of life.

The tension between reality and imagination is fragile in Calvin and Hobbes, and Watterson fought hard to preserve its integrity. As the series soared in commercial success, syndicates wanted to merchandise the characters as dolls, t-shirts, mugs—Bill said No:

… the more I thought about what they wanted to do with my creation, the more inconsistent it seemed with the reasons I draw cartoons. Selling out is usually more a matter of buying in. Sell out, and you’re really buying into someone else’s system of values, rules, and rewards.

Underneath this anti-corporate message is a deeper one: each of us lives by a system of values, which is either our own or someone else’s. Maturing is about finding one’s innate sense of right, wrong, and beautiful.

This is why I love art made for children: it sheds the layers of adult life that cloud our inner world, revealing the artist’s sense of what sparkles with meaning. As the religious trope goes, the eyes of children are the clearest.

At the peak of his success, Bill Watterson ended the strip, saying simply, “I believe I’ve done what I can do within the constraints of daily deadlines and small panels.” Here he is five years later:

Since Calvin and Hobbes, I’ve been teaching myself how to paint, and trying to learn something about music. I have no background in either subject, and there are certainly days when I wonder what made me trade proficiency and understanding in one field for clumsiness and ignorance in these others.

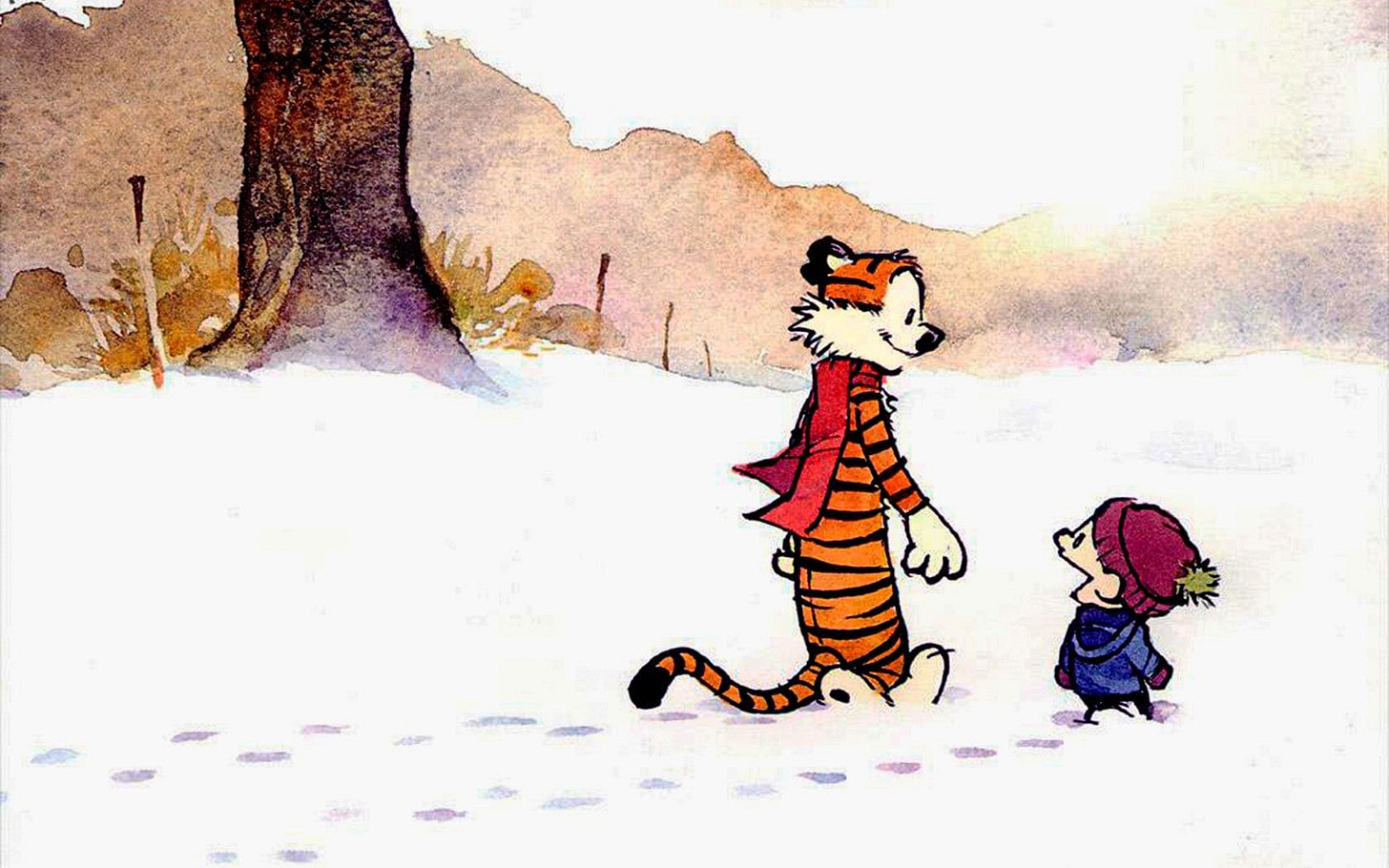

Faced with the end of adulthood, which is a kind of death, he chose infancy.

2 – Clouds pass by

I’ve kept her slippers by my bed. They’re the last remnants of a story about two entwining lives—one which, in the end, was mine alone to hold onto.

The fragile balance of fantasy and reality has been shattered.

As I settle into a new reality, and perhaps new fantasies as well, I need to reconsider who I am and what I stand for in light of life’s unpredictability. What do you choose to value when what you clutch to your chest—alive and precious and full of possibility—can be ripped away?

It’s quiet in my room. I’ve spent a lot of time here in the past weeks. This time, I put on “Cais” by Milton Nascimento.

The song opens like a sky. Nascimento’s dreamy Portuguese moves overhead, and though I don’t understand him, I feel like he’s speaking to me. Later, I look up the translation:

For those who want to let go

I invent the pier

I invent more than what loneliness gives me

I invent a new moon to brighten

I invent love

And I know the pain of throwing myself

I see the Sunday Pages sitting on my shelf, and it makes me wonder: what does it take to throw myself at life like that?

3 – A bird in the hand

Thrown out of the Subway into Bay Ridge, it’s a different world. A woman shoots from the store onto the crowded sidewalk, braids coiled heavily on her head, crate swung over her stomach. She weaves her way elegantly, forcefully, without looking to either side. She seems to say: I do what I have to do to live.

Two men in black baseball caps and ill-fitting clothing hobble up the sidewalk, one holding the other by the arm to keep his sick companion upright. The supporting one, heavy with sadness, makes brief, pleading eye contact with me.

A woman in high heels, dyed red hair, and a hardened scowl caked in makeup hurtles past me, black see-through dress flapping in the wind. Her message is clear: my sex is my armor.

Everyone carries a message.

A man walks up to me while I’m taking this note, beckoning sincerely if I can spare a dollar. I tell him that I don’t carry change. He smiles politely and walks off with a nervous look about him, peering into stores. A sense of regret overtakes me.

A pigeon swings down in an arc that echoes the hanging wires. Another follows. It’s a wonder that we find one another in this world. It’s a wonder that we find any kindness in ourselves to extend.

“Something in the friendship between Calvin and Hobbes seems to hold a small piece of truth,” Watterson writes in his introduction to The Sunday Pages. “Expressing something real and honest is, for me, the joy and the importance of cartooning.”

Real and honest—I can buy into those values.

But how do you hold a piece of the truth without crushing it in your hands? (My cello teacher used to tell me to grip the neck of the instrument like a small bird is sleeping under my thumb.)

4 – Lançar

I asked my good friend Chat Gepetto1 if there were any Portuguese subtleties I may have missed in “Cais.” Here’s what xe said:

“Invento o cais” – Literally, “I invent the pier,” but “cais” can symbolize a place of departure, arrival, or refuge. In English, “invent” might feel unnatural, whereas in Portuguese, it suggests creating a metaphorical place of safety or transition.

For the past month, I’ve considered blowing up my life and rebuilding it from scratch—but in the time since, I’ve realized that it’s not a matter of building a fortress. It’s tempting to withdraw, but I need to invent my pier. I need to lançar:

“Lançar” (to throw/launch oneself) conveys a mix of courage and vulnerability—something like taking a leap of faith or surrendering to an experience. English lacks a single verb with this emotional depth.

How do I live by my own set of values, with courage and vulnerability?

In Escaping Flatland, Henrick Karlsson writes about applying design principles to life. When you design anything—a building, a law, a relationship—you work to deeply understand the context, then you chip away at the form until you have a good fit.

Life isn’t static, so you can’t think about it as a game to win.2 It’s an ongoing process that you find your place in. So if I want to find a life, a vocation, a relationship that fits my values, the answer may be as simple as throwing myself at different contexts and seeing what sticks.

I’ve decided to build my pier further out into the water—both in life and online—and see what kinds of wanderers and creatures come to roost.

The name of this newsletter, Long Life, comes from an improvised piano song in which Lyle Mays resolves a tricky, tangled chord. It’s about being thrown into a hurricane and finding the path at the center.

As Milton Nascimento would say,

“Tenho o caminho do que sempre quis” – “I have the path to what I’ve always wanted.” It suggests both possession and discovery.

I don’t have any answers—but I have a path.

Let’s go exploring! ✤

This is a Jordan Jensen joke, not an original

Check out Finite and Infinite Games by James P. Carse if you want to read a mathematician waxing poetic on this idea

Remember that as you step out into your pier, you always have a home to come back to!